Why it’s so difficult to get on the ballot in L.A.

By David Zahniser for LA Times

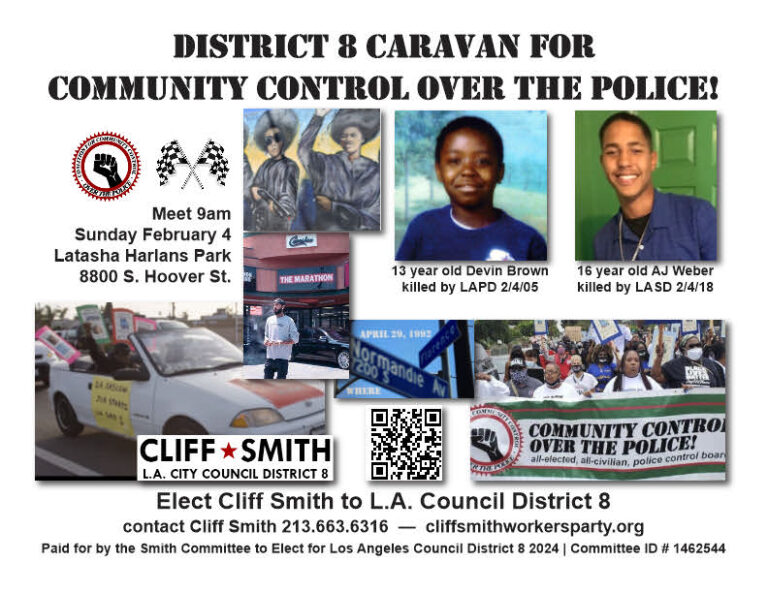

Union leader Cliff Smith had big plans for 2020. He was going to launch a bid for a seat on the Los Angeles City Council, then wage a campaign focused on such issues as police misconduct and the need for public housing.

The campaign never got off the ground. Why? Smith, the business manager for Roofers & Waterproofers Local 36, failed to get the 500 signatures he needed to qualify for the ballot.

Now he is trying again, knocking on doors and chatting up shoppers outside supermarkets in the 8th District, which takes in a big chunk of South Los Angeles. He is determined not to fall short a second time.

“It’s not easy — at all,” Smith said. “But the conversations are productive.”

As we’ve mentioned in this column before, L.A. can be an extraordinarily difficult place for local candidates to qualify for the ballot. Four years ago, more than a third of the people who took out petitions for seats on the L.A. council or school board — 18 out of 51 — did not make it past the signature-gathering process.

That’s due, in part, to the fact that rules set up at City Hall are more restrictive than those that apply to many other political offices in Southern California. In L.A., council candidates must collect at least 500 signatures from registered voters who live in the district where they are running.

Had Smith decided to wage a campaign against county Supervisor Holly Mitchell,who is also running this year, he would have needed to collect just 20 valid signatures and pay a $2,324 fee. Since each supervisorial district has about 2 million people, finding those voters would have been a breeze.

If Smith were running for district attorney, he also would have needed at least 20 voter signatures. Because the D.A.’s annual salary tops $400,000, he would have had to pay a larger fee, or just over $4,000.

Some at City Hall say L.A.’s ballot rules make sense. After all, they argue, if a candidate can’t manage to persuade 500 voters to sign a petition, how will they ever secure the votes to win public office?

Others say the regulations lock too many people out.

Eduardo “Lalo” Vargas, a schoolteacher hoping to unseat Councilmember Kevin de León on L.A.’s Eastside, said the city’s ballot requirements favor candidates with serious money, especially incumbents. Candidates with greater financial resources have the ability to hire staff to help with their signature-gathering efforts, Vargas said.

“This kind of process doesn’t really favor a working-class, grassroots candidate like me,” he said.

De León, now running for reelection, was the first to qualify for the ballot in his race, which has drawn interest from 13 other candidates. In a victory lap, De León, thanked the people who volunteered to collect signatures.

“Your unflinching support speaks volumes about the work we’ve accomplished together,” he said in a campaign email.

City Clerk Holly Wolcott, whose office reviews the candidate petitions, has taken major steps to help political newbies find their way onto the ballot, posting a video on the city’s website that lays out the rules. According to the video, those who want to avoid the city’s $300 filing fee must turn in 1,000 signatures, instead of the already difficult 500. Few people take advantage of that opportunity.

The video makes clear that there are a number of ways to screw up. A volunteer who fails to follow the city’s very specific rules could cause an entire page of signatures or more to be disqualified.

Jillian Burgos, an optician running for a council seat in the east San Fernando Valley, said she expects that the City Clerk’s office will deem at least some of the signatures she turns in as invalid. For that reason, she is planning to have hundreds of extras when she turns in her petitions.

“Ideally, I would love to get 800,” she said. “I will be happy if we get 700.”

Smith, the roofers union leader, turned in 920 signatures in 2019, which made it only more crushing when he had only 458 valid ones. Many of those that were disqualified came from people who were registered to vote in the 8th District, but entered addresses different from those that were in the voter registration file, he said.

Smith, 53, attributed that phenomenon to the fact that the district has a large share of renters who move from apartment to apartment.

If Smith succeeds, he will almost certainly face City Councilmember Marqueece Harris-Dawson, who is running for a third and final term. In 2020, Harris-Dawson was the only candidate in his race to qualify for the ballot, which assured him a smooth path to reelection.

Harris-Dawson, in a statement, said he appreciates the other candidates who are looking to enter the race. The district, he said, needs more advocacy to “combat the disinvestment we’ve experienced for decades.”

“Having multiple candidates and conversations about how our district moves forward is a great thing,” Harris-Dawson said.

Three others in Harris-Dawson’s district — real estate broker Jahan Epps, community activist Tara Perry and city employee Shawn Yarbrough — have also taken out candidate petitions.

The deadline to turn them in is Dec. 6.